UNDER THE SURFACE | Australia’s fine-wine ambitions

British by birth, Andrew Caillard MW is one of the most authoritative wine commentators in Australia. Co-founder of auction house Langton’s, the author of several wine books, and producer of films including Red Obsession and Blind Ambition, he has, through his three-volume, 1,760-page Australian Ark, created the most extensive history of Australian wine ever written, lauded as ‘a masterpiece’ by winemaking luminary Brian Croser. Having hosted its London launch at the Club, he gave us his thoughts on the narrative of Australian wine.

When, aged 22, I arrived in Australia by container ship at Sydney’s Botany Bay in December 1982, I possessed two post-school qualifications: a Wine and Spirit Education Trust Higher Certificate, and a Steering Certificate to drive a ship over 150 tons, the latter earned on my passage through the Pacific Ocean on the MV Tolaga Bay. Soon after, I was interviewed for a place at Roseworthy Agricultural College, and in March 1983, I began its Wine Marketing course. Although I was unaware at the time, both my cousins had studied winemaking at Roseworthy some years before.

My great great great grandfather, John Reynell, had landed in Australia in 1838, and went on to become a winemaker. There are surviving vines in Australia that date almost as far back, planted a decade after the accession of Queen Victoria – and yet their story hasn’t really been told. Even more shockingly, we still refer to Australia, in winemaking terms, as the ‘New World’.

The country’s first wine was made in 1792, and the story of Australian wine is profoundly connected with the earliest days of settlement in New South Wales; the first vineyards were planted and tended by convict labour, and it was not unusual for local First Nations people to assist in the agricultural work. Colonising settlers and explorers saw the Australian continent as a potential source of great agricultural and mineral wealth. And while wine has never achieved the same kind of wealth as wool, coal and iron ore, it has always been near the centre of influence and power.

‘At the famous Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855, many scientists predicted that Australia would become the France of the

andrew caillard MW

Southern Hemisphere’

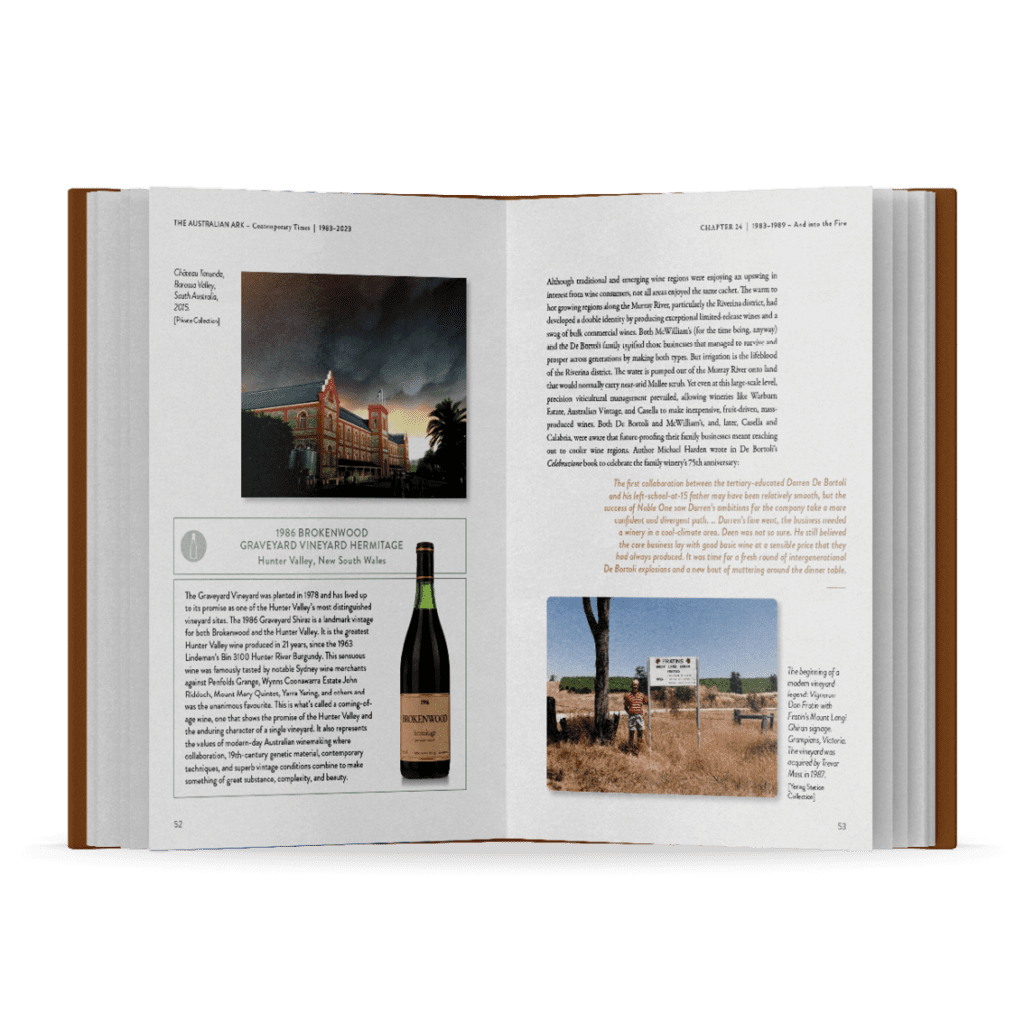

Our forefathers’ ambition was to make fine wine, not commercial wine. It was all interconnected with the British Empire, which propelled the economic prosperity and development of the industry from 1788 for 150 years. After the success of New South Wales wine at the 1855 Paris Universal Exhibition (the same exhibition at which Bordeaux’s 1855 classification was formed), many scientists from a variety of disciplines, but with an interest in wine, predicted that Australia would become the France of the Southern Hemisphere. This may appear fanciful, but the subsequent rampant destruction of European vineyards by the aphid-like pest phylloxera during the 1860s and 1870s led to a massive expansion of colonial wine into export markets in the late 19th century (the first list of the UK’s Wine Society, which this year celebrates its 150th anniversary, included Kirktons Red from New South Wales and Auldana Red Superior from South Australia).

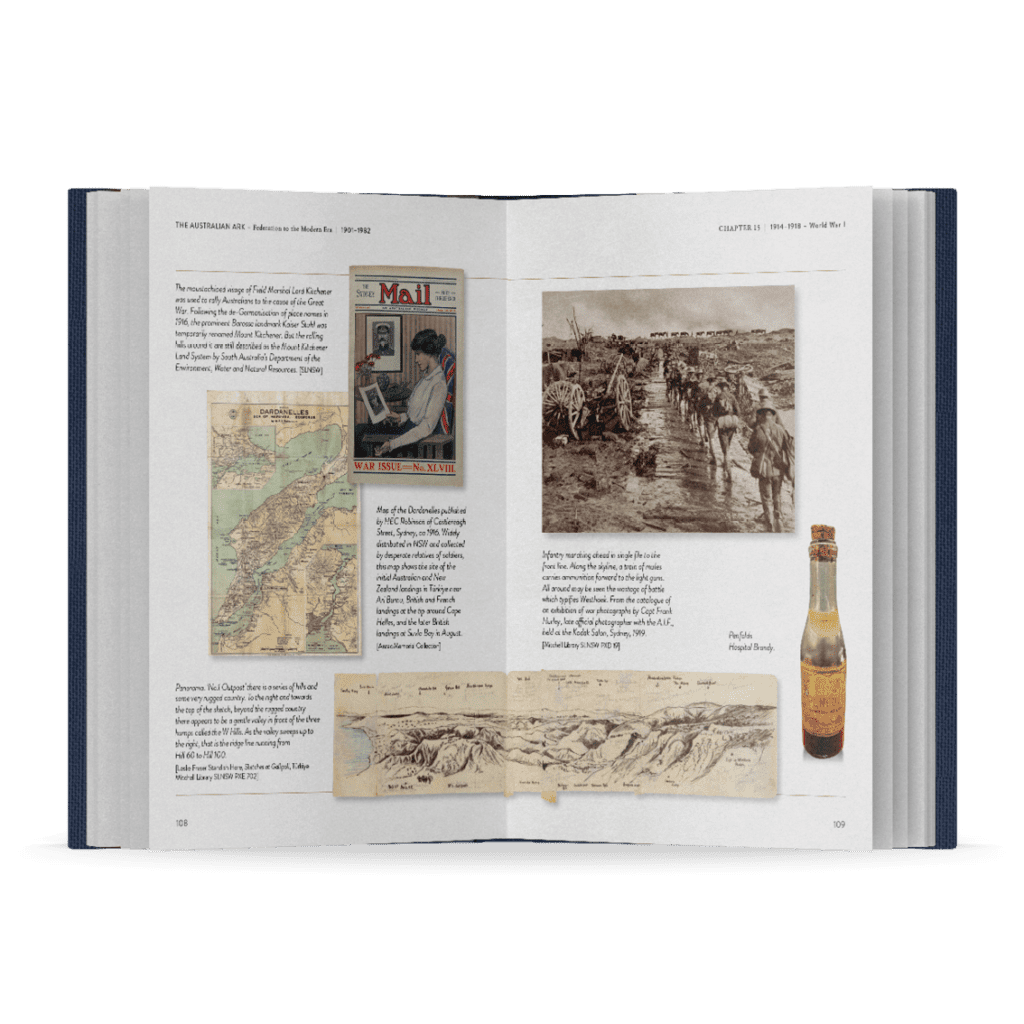

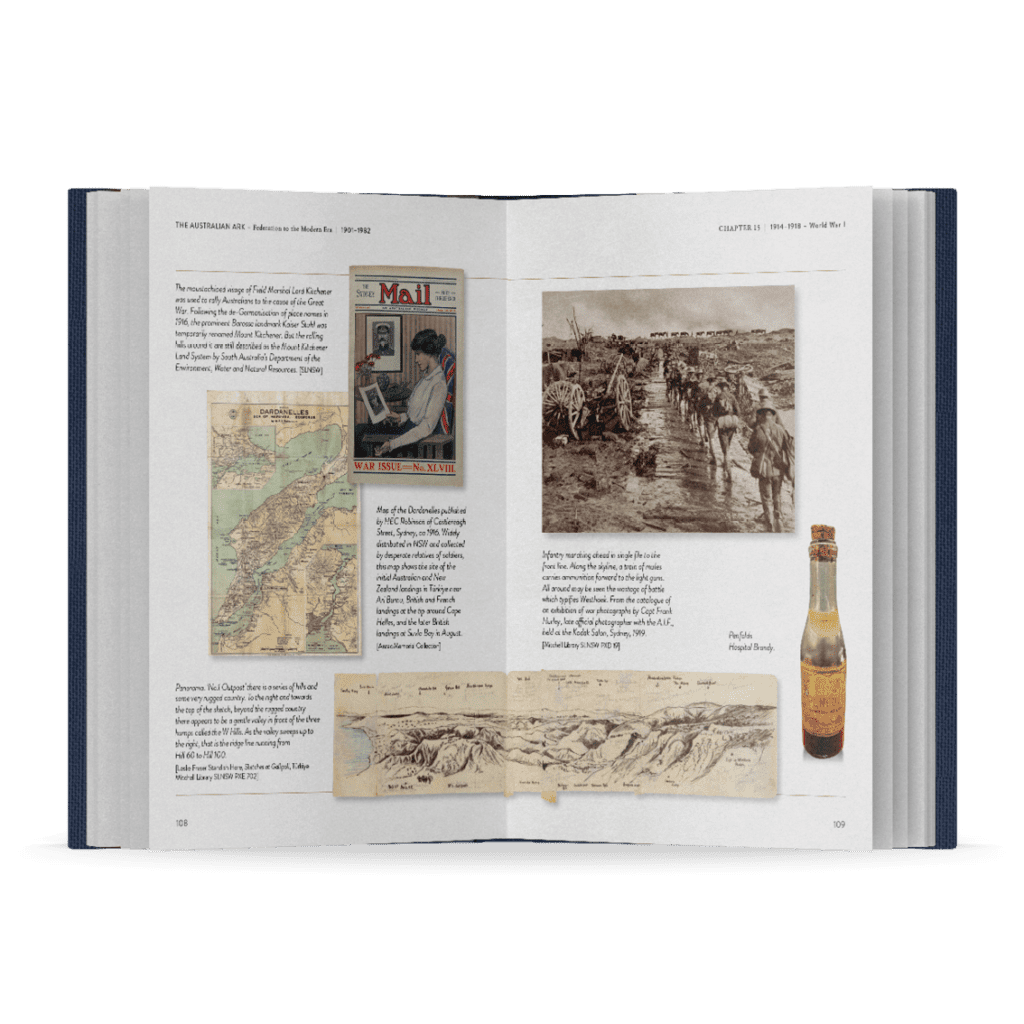

Alas, World War I changed everything. Sixty thousand Aussies died fighting for the empire, and the influenza pandemic of 1920 took a further toll. After that, the Australian government promoted fortified wine production which, while beneficial financially, diminished the reputation of still wines at home and abroad, from which it would take years to recover.

Many vignerons went to war and their fates transformed the destiny of Australian wine. My own forefathers John, Walter and Carew Reynell were notable South Australian vignerons whose aspirations, successes and misfortunes I learned of as a child growing up in the UK. When I arrived in South Australia for the first time, the ghosts of family past were palpable to me. Two world wars had destroyed their dreams.

While many went to fight, men with reserved occupations were obliged to stay at home on account of their importance to the economy. One such individual was Ray Beckwith, who held the position of ‘chemist’ with Penfolds (today we would call him an oenologist). Penfolds winemaker Max Schubert was obliged to go off to war, but would return unscathed at just the time, in the late 1940s, when science and technology combined with a changing society to enable him and Beckwith to develop pristine white wines and to create Grange Hermitage. It was a Sliding Doors moment. In the 1950s, a revival took hold as the industry was forced to redefine itself, adopting new technologies and creating new expectations for fine wine. It was the start of modern Australian wine.

Over the last 70 years, Australia has defined itself, and developed a confidence to believe in its own voice and adapt to the spirit of our times. Personally, I find the endless acquisitions and corporate takeovers of the Australian wine industry rather boring – family companies generally take a much longer-term view. The succession of younger generations at Brown Brothers, Henschke, Leeuwin Estate, Tyrell’s and Yalumba give a feeling of continuity and purpose. That said, Australia’s largest corporate wine companies have played a critical role in building the industry’s reputation and success – with Penfolds one such success story.

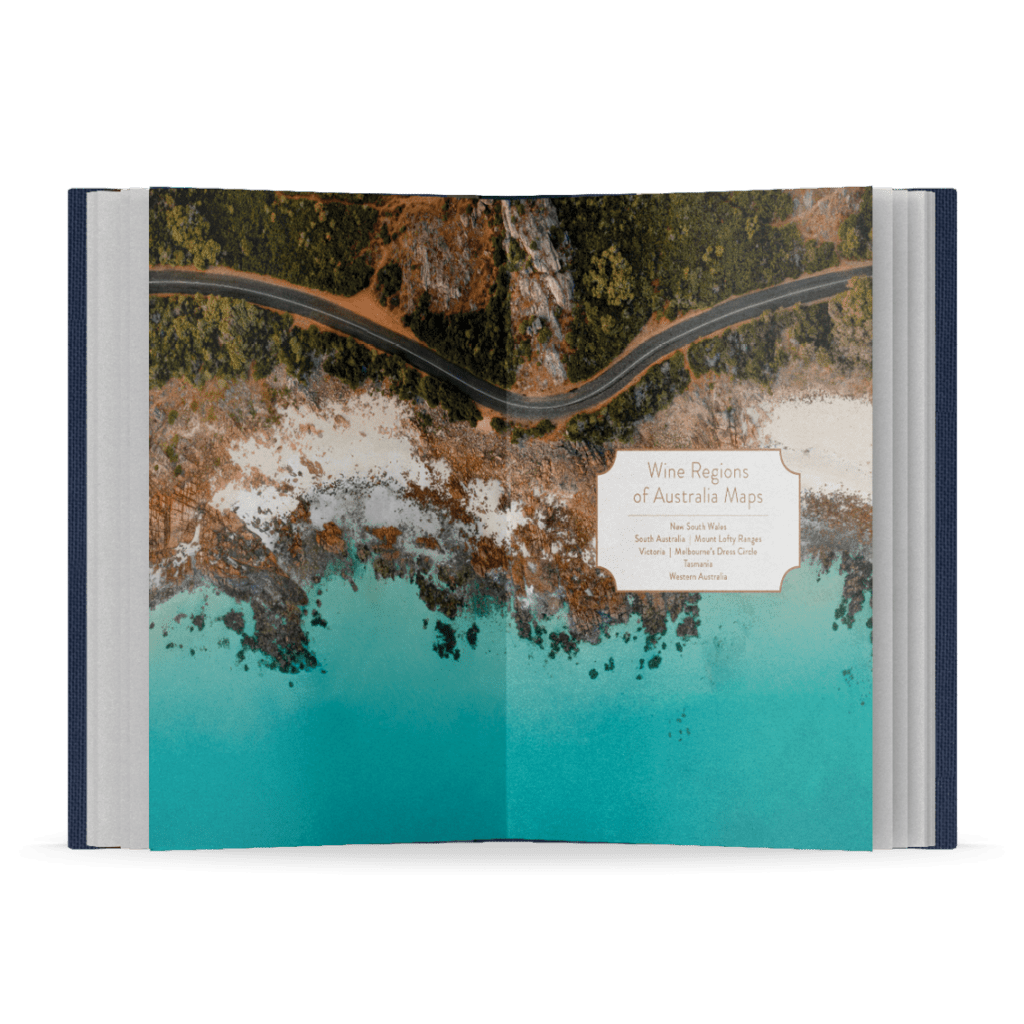

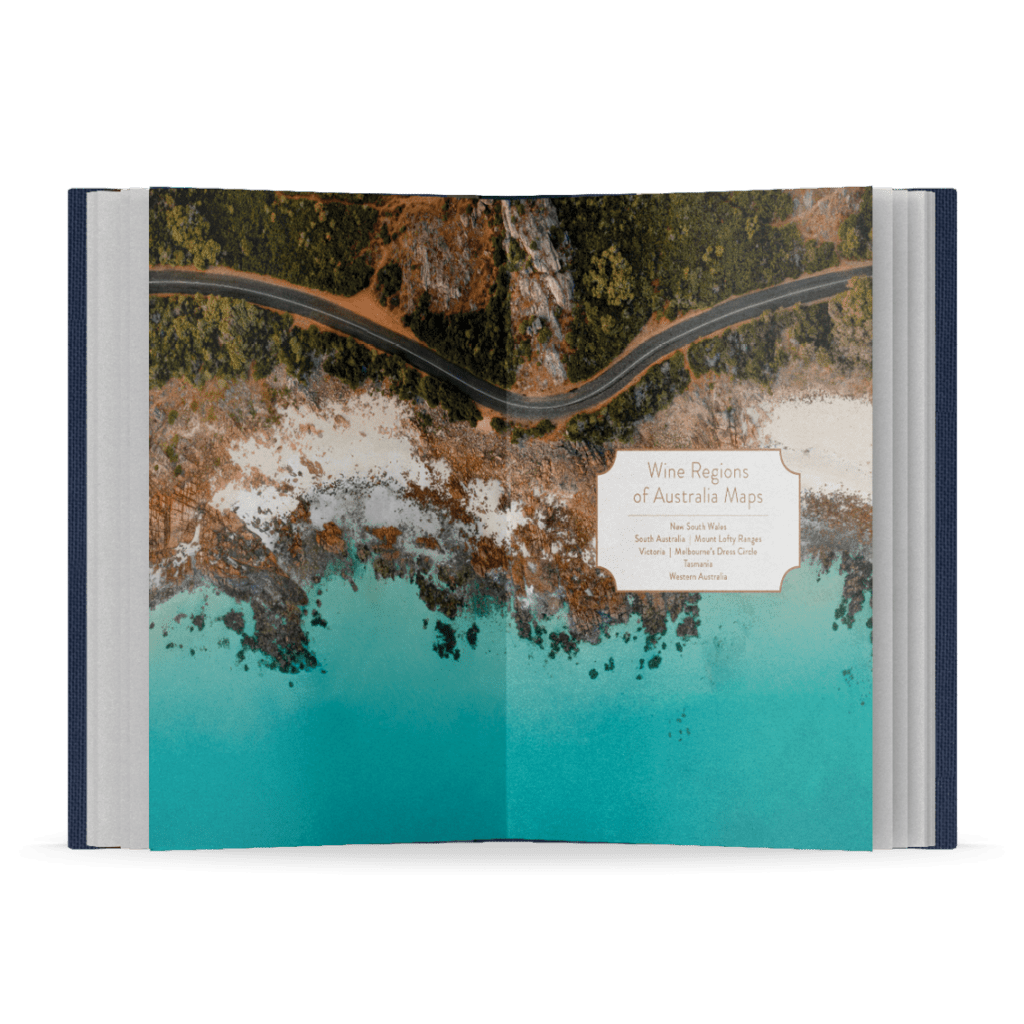

Much more interesting to me, however, is the country’s viticultural ancestry. Australia still possesses the largest acreage of 19th-century-planted vines in the world, representing a living symbol of the era’s ambition and foresight. Most of Australia’s surviving 19th-century vineyards are in South Australia, which has never been invaded by phylloxera. But ancient vineyards have survived in the Hunter Valley, Great Western, central Victoria and Swan Valley, a heritage that includes ancient genetic vinestock. In my history of Australian wine, The Australian Ark, there are 16 pages alone devoted to listing all the country’s old vines, going back to the 1840s.

When I started the project 18 years ago, I had a modest vision to write a book on the classic wines of Australia. As an auctioneer at the time, it seemed like a good thing to do, because I lived among bottles of living history, and knew much about their stories and the people who made them. By accident rather than good planning, it rather grew in scope, evolving into as much of a history book as a wine book – a social, political, cultural history of Australia told through the prism of wine. 15,000 words became 50,000 words and then eventually around half a million words by the time of publishing.

Ultimately, the Australian Ark is about ambition, courage, hard work and generations of effort to build an industry of great value and meaning. The Australian wine industry is going through a tough time right now, and its reputation should be a lot higher, given that we are living through a golden age of viticulture and producers are making some of the finest wines in their history. Sadly, the narrative is driven by the marketing of volume producers and the size of the more commercial market. We must work hard to push back against ill-informed viewpoints, ignorance, indifference and schadenfreude. And this can only be done by believing in ourselves, being aware about where we come from and having a feeling of purpose. Australians are a resilient lot, and I’m very optimistic about our ability to reinvent.

I am hoping this book begins a fresh conversation about Australian wine and helps the industry progress through this century with optimism, energy and foresight. Our history is so colourful that every wine business, old or new, can harness strands or connections to build richness and longevity into their stories – because we all belong to a tradition that goes back almost 250 years.

The Australian Ark is distributed in the UK by the Academic du Vin Library. Members of 67 Pall Mall can access a £10 discount by using the code AU67PM on its website: https://academieduvinlibrary.com/products/the-australian-ark

IN

THE

VINEYARD

Gump Hof, Alto Adige, Italy