WHAT I’VE LEARNED | Ernst Loosen

13 November 2025

Erni Loosen is best known as the saviour of German Riesling, having transformed the reputation of the category through his Dr Loosen family estate in the Mosel. In the 1990s, he took over the JL Wolf estate in Pfalz, which marked his expansion into Pinot Noir. Today he makes wine with partners in Oregon, Washington State and Australia, and recently bought part of Vieux Château de Puligny-Montrachet in Burgundy, from where he makes a range of wines via a negociant model

‘Both my mother and father inherited wine estates, but they were completely different. My mum’s estate, from the Prüm family, only made sweet wines. My father’s family produced only dry wines – they thought sweetness ‘enveloped’ the wine. Today we have these two different traditions, both of which we still follow.’

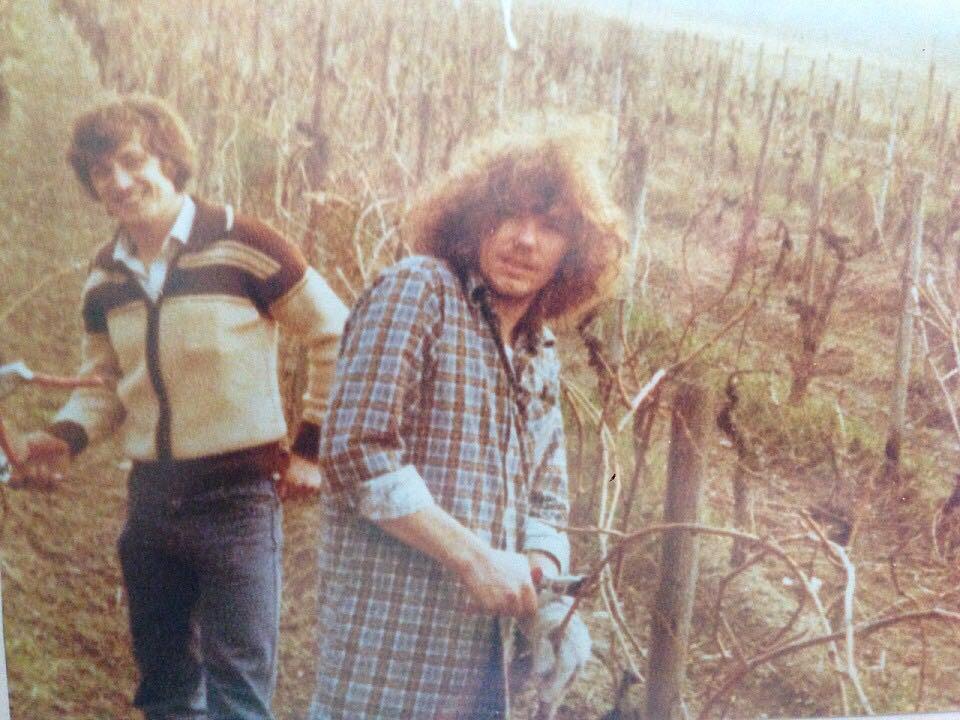

‘My father was a lawyer and a politician, and the winery wasn’t a major focus for him. But he felt I should study winemaking at Geisenheim [the renowned German wine school] and he didn’t like to be challenged, so I went along with it. I had a great time, but I don’t think I went to a single lecture. Me and my flatmates would get up at noon and then starting discussing what to have for dinner…’

‘I had a difficult relationship with my father. I couldn’t ever envisage working with him. So after Geisenheim I went to the University of Mainz to study archaeology. But it’s difficult to make a living as an archaeologist. And then my father suddenly became very ill, and my mum called me, my three brothers and two sisters together and told us we each had the chance to take over the wine estate, otherwise she’d sell it. My brothers and sisters pushed me to take it on. That was 1987, and the winery had twice as much debt as turnover.’

‘During the ‘80s, the German wine industry was in a terrible state. The only thing it was known for was cheap Liebfraumilch – Blue Nun and Black Tower. I came to the UK in 1983 with my father, who was looking for an importer. We stayed in a bed and breakfast, and I stocked up on coins and used a payphone to call all the wine importers I could find in the Yellow Pages. Those were the worst three days of my life. No-one wanted to touch German Riesling – they couldn’t even contemplate it as a serious wine. All they wanted was Chardonnay.’

‘When I took over, we had to improve quality, which meant reducing yields through more scrupulous selection during harvest. But the workers didn’t like the idea, as it involved more work, so they walked out. That actually turned out well for me, as I had wanted to sack them, but couldn’t afford to pay them off.’

‘The surprising thing to me was how relatively simple it is to make a great wine. A lot of work goes into it, of course, but the process is not complicated. You just need to pick good-quality fruit, maintain a clean cellar, and let nature do its work. The real challenge is in selling the wines.’

‘In the late 1980s, when my importers organised tastings, it would be me and three old ladies. Today we sell out and have to turn people away. It’s very satisfying, but it took 20 years to achieve.’

‘Riesling’s brilliance lies in its versatility – from the dry to the noble sweet. You can’t do that with Chardonnay. But Riesling’s versatility is also its downfall. People are sometimes not sure what they’re going to get – is it dry, medium-dry, sweet… so they are wary. But for people who get it, it’s the greatest grape variety on Earth.’

‘There’s no other region in the world that can produce a wine like a Kabinett-style Mosel Riesling. It’s fantastic. It has fruitiness and lightness, and this great tension between acidity and residual sweetness, all at 7.5-8% ABV. It’s a totally different dimension of wine.’

‘As a winemaker, you have to give as much – if not more – attention to the cheapest wines as the top wines. My father’s generation put all their focus on the top wines. But those look after themselves. It’s the entry-level wines that need the work – and if you make those as good as possible, success follows. So our Dr L wines get the same attention as our Grosses Gewächs.’

‘People think global warming means vineyards turning into deserts. It’s true, temperatures are rising and we have earlier harvests. But you have to look at it across the whole year. We’re having warmer winters, but last year we were struggling to get the grapes ripe. Spring was up to 30˚C, and then the whole summer was cold and rainy. Everything is changing.’

‘There are so many viticultural ways to fight global warming. I know that journalists don’t like to hear it, but it’s true. We were always told that the lower the yield, the better the wine. And that was true in the cold vintages of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, when you couldn’t get the grapes ripe. But today in Washington State, we get much better Riesling – more aroma ripeness, but not too much sugar ripeness – through higher yields and longer hang time [the time grapes spend on the vine to achieve flavour ripeness as well as sugar ripeness].’

‘I first met Peter Barry [second-generation owner of Clare Valley producer Jim Barry] at the London Wine Fair in the mid-‘80s. The best party back then was held by the Australians at Kensington Roof Gardens and he would sneak me in. In 2016, after I’d known him for 40 years, I said to him: “Do you know what, Peter, I’d really like to make a Riesling in Australia.” But I told him that it had to be made in the traditional German way, the way my great grandfather made them, with indigenous yeast fermentation, aged two years in the barrel, on full lees, without battonage.’

‘I sent over a 3,000-litre barrel, and Pete and his team were fine with everything, until I said it had to be under cork. They went very quiet and eventually called me and said, “Look, Erni, we’re Australians. We can’t go back to cork.” So I said, “But we agreed to it – I’ve ordered the corks and sent them to you.” As it got closer to bottling, they got more and more nervous and just said it was impossible. It seems with cork, there’s this Aussie mentality that they can’t get past. So we didn’t use it.’

‘People always ask which other Rieslings I like. To be frank, I always found Australian Rieslings too austere. They’re all bone dry, with high acidity and this strange limeiness. I don’t know what it is but it’s always there. It’s not in our wine that we make there [the Wolta Wolta Riesling], though. It’s a completely different animal.’

‘Today we use that same traditional German winemaking approach with our top Rieslings everywhere – Appassionata in Oregon, XLC [standing for Extended Lees Contact] in Washington State… But what I don’t like is this idea of blending wines from different countries, like the Jaboulet-Penfolds tie-up. I’m a purist, and that sort of thing has absolutely nothing to do with terroir.’

Not a 67 Pall Mall Member? Sign up to receive a monthly selection of articles from The Back Label by filling out your details below

TWO

MINUTES

WITH

Julio Sáenz, La Rioja Alta

UNDER

THE

SURFACE

The magic of Musar

MEET

THE

SOMM

Gastón Adolfo