UNDER THE SURFACE | The magic of Musar

17 December 2025

Chateau Musar holds a special allure for many wine lovers, both as a producer and a wine. On a recent visit to the London Club, Marc Hochar of the owning family spoke to Guy Woodward about the Lebanese trailblazer’s singular place in the wine firmament

There are many aspects to Chateau Musar which are unconventional. At a sold-out tasting of the Lebanese producer’s wines at the London Club this autumn, the rapt audience, while seduced by the signature exoticism of the wines, picked up on their inconsistency. It was a facet that went beyond vintage variation to bottle variation. Host and Musar co-owner Marc Hochar was breezily unapologetic.

‘Every vintage is different, every evolution is different and every bottle will be different – even if it’s the same wine.’ Pushed as to whether consumers shouldn’t expect a certain degree of uniformity in such wines, Hochar was unabashed. ‘If you want consistency, drink non-vintage Champagne. Lots of people love that. But that’s not how we perceive wine. We don’t do “copy-paste-repeat”. We can’t. Maybe because of where we live, our heritage, our environment. It’s a philosophy, a way of life.’

Such challenges have been a

constant in subsequent years.

In several vintages, picking

dates have been partly

informed by conflict

That unpredictability is inherent in Musar’s identity, in its very existence, even. It is a fragility that helps defines the wine itself. Certainly Musar is known for the extravagant evolution of its signature wine – both in the glass and in the bottle – a wine which Oz Clarke heralds as ‘paradoxical, always changing’. For Hochar, that’s part of its appeal. ‘When you start your day,’ he told 67 in a separate audience ahead of the tasting. ‘Do you want to know exactly what’s going to happen that day? It would be a very boring way of life. Unliveable, I would argue. It’s the same with wine. I would hate to always taste the same wine and never have something new. It’s not my character. In the end, the winemaker puts his imprint on the wine, and my father was the same. He was all about enjoying food, wine and embracing surprises in life. Surprises that bring you joy, and yes, also sadness. But he loved that unpredictability.’

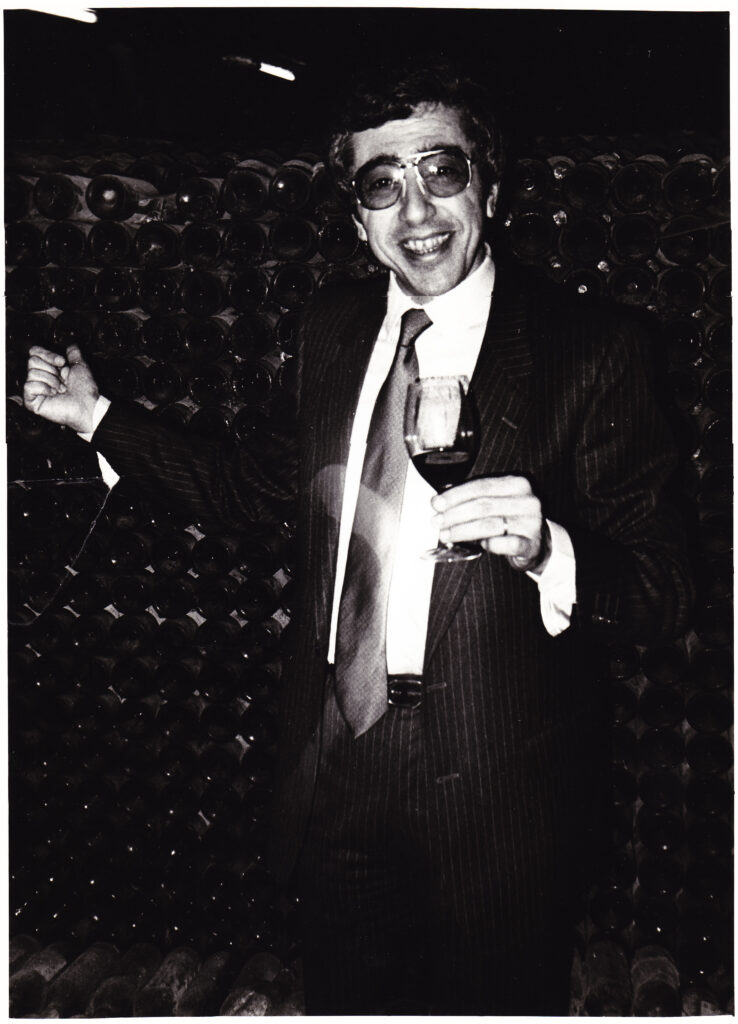

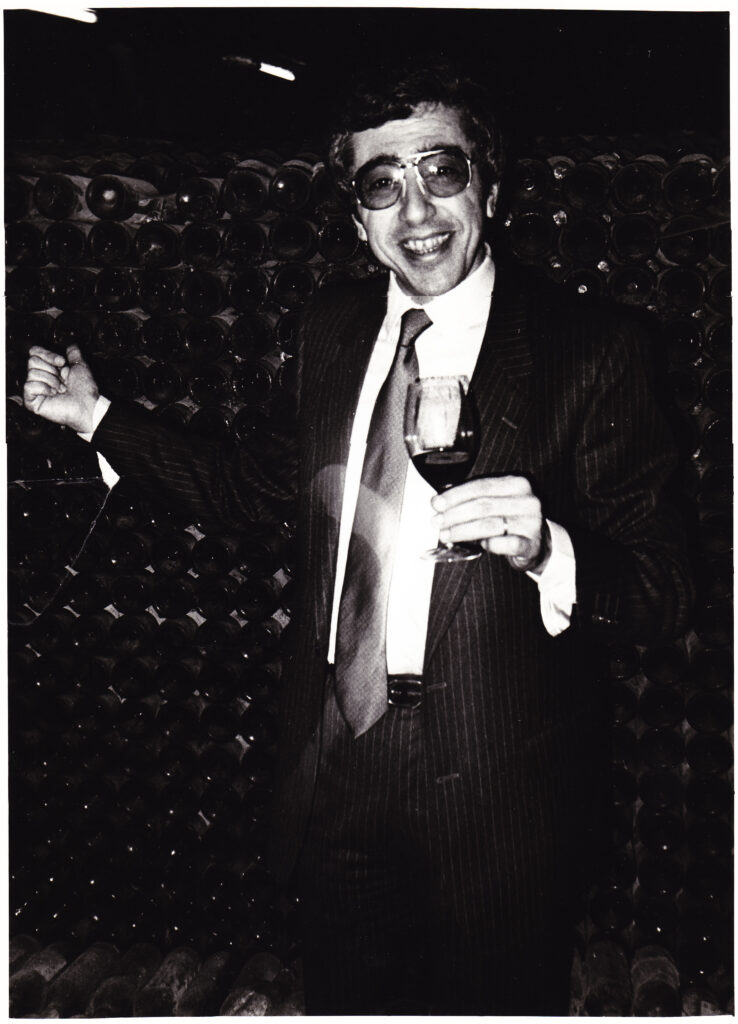

Marc’s father, Serge Hochar, was the force behind the emergence of Musar onto the international scene. His father Gaston had founded the winery in 1930, planting vineyards in the Beka’a Valley, the bread basket of what was then a new country, with the winery established in an old convent just outside Beirut (Gaston felt it should be in a Christian area). In 1960, he asked his son to join him in his endeavours. The 20-year-old Serge, an engineering student at the time, declined three times before eventually accepting his father’s offer, with one condition: ‘You leave.’

‘My father wanted to be able to create wines in his own way,’ explains Marc. That way was essentially non-interventionist: natural yeasts; no fining; no filtering; minimal sulphur. Like his father, Serge had no winemaking know-how, but to him it made no sense to add things to the grape juice that were not originally there. ‘If the Phoenicians could make wine that way 6,000 years ago, why can’t we?’ was his reasoning.

What he didn’t know, of course, was whether he could make good wine that way. But he was determined to find out. After a few years of trial-and-error winemaking, Serge headed to Bordeaux University to spend two years studying with the eminent professor Emile Peynaud, who taught him more conventional vinification lore. And while Serge harnessed some elements of his learnings on his return to Lebanon in 1966, by the 1970s he had returned, largely, to a non-interventionist approach. So much so that when Peynaud expressed his admiration for the wines on a visit in the early ’80s, Serge admitted that he had done the exact opposite of everything he had taught him. Peynaud took it well, says Marc. ‘He said it was all about applying that knowledge to your land, your terroir, your environment. You had to learn the rules to know when to break them.’

Ultimately, he adds, the Musar philosophy is that nature can do better than humans – even if that comes with inherent inconsistency. ‘I like wines that have this ability to change and not be only about fruit. Fruit is a simplistic version of what wine can be. Secondary, tertiary aromas – that’s the bottom part of the iceberg.’

It was that complexity that caught the eye of the late Michael Broadbent at the Bristol Wine Fair in 1979. When the august writer, head of Christie’s wine department and Bordeaux devotee crowned Musar his ‘find of the fair’, his praise couldn’t have been better timed. Domestic sales had plunged after the outbreak of the long-running civil war, so export markets were the major focus for Musar, whose against-the-odds story also caught the imagination of the wider media. In 1984, Serge was named Decanter’s first ‘Man of the Year’ (an award since rebadged as the magazine’s ‘Hall of Fame’). ‘All of a sudden, people were curious,’ says Marc. ‘They were talking about varietals blended in a different way to anywhere else, in a region that, to most people, was new – and a region that was known for bloodshed.’ By the end of the Civil War in 1991, Musar’s entire sales were exports.

The 1984 Musar was the famous ‘truck-fermented’ vintage. At the height of the fighting, the various roadblocks and checkpoints that had been set up meant transporting the grapes from the Beka’a Valley to the winery via a circuitous route through the mountains. What should have taken three hours took five days. And because Serge Hochar’s approach was simply to pile the bunches of grapes on top of one another in open-top trucks, with no refrigeration (as is still the case), nature took its course. ‘The wine tasted like Madeira,’ says Marc. The vintage wasn’t initially released, but, astonishingly, it eventually evolved into a rich-yet-elegant wine, approaching a dry Banyuls in style. When it was finally released 30 years later, the family described it as ‘sticking two fat fingers up at the twisted egos, tortured logic and misplaced hubris that cause men to fight and kill’. It soon became something of a collector’s item.

Such challenges have been a constant in subsequent years. In several vintages, picking dates have been partly informed by conflict. In 2006, during conflict with Israeli forces, a large Musar flag was placed over the grapes to ensure the trucks wouldn’t be mistaken for anything more threatening on their voyage to the winery. Last year, when Israeli forces invaded southern Lebanon, the harvest was brought forward to avoid the worst of the shelling.

How does one become inured to such jeopardy? How does one ask one’s team to deal with such danger – the people who are picking the grapes, driving the trucks? Pragmatism, it seems. ‘You could be sitting at home, going about your daily life, or you could be at work in the fields. In both cases, there’s a risk.’

The appeal of Musar lies not just in heroic winemaking, however. The wine itself defies expectations. ‘People perceive Lebanon as a very warm country and therefore not necessarily the best place to produce elegant wines,’ says Marc. ‘But we are at altitude, we don’t irrigate, and we have extremely low yields.’ The result, he says, is a rare marriage of intensity and acidity that yields the magical, savoury complexity that defines it.

There is also a misplaced perception – possibly because of the way the wine evolves, possibly because of the link to the region, first established when Ronald Barton of Château Léoville-Barton became friends with Gaston Hochar when stationed in Lebanon during WWII – that Chateau Musar is a Bordeaux blend. It is actually a roughly equal blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cinsault and Carignan – a combination that is, to say the least, unorthodox.

Climate change means Cabernet is on the wane in favour mainly of Cinsault, while the team has also turned to Tempranillo, planted 12 years ago and blended with Cinsault and Cabernet for its Levantine cuvée (first vintage 2017). Every year 20-30% of the crop is lost to heat, though for the timebeing, irrigation is still not being considered as a solution. ‘What we lose in quantity we gain in quality,’ says Marc. They are hoping to be able to slowly increase their holdings from the current 200 hectares, which yield an annual average of 600,000 bottles, 85% of which is exported.

When Musar began exporting, in the early 1980s, Lebanon had five wineries. Today there are around 60, though only half the country’s total production of 10 million bottles goes overseas – roughly the same as a good vintage of Dom Pérignon. Production of Musar will never be huge. ‘We don’t make wine for people’s palates,’ says Marc. ‘For 25 years, no-one understood the white wine [a lightly oxidative blend of the native – and resolutely uncommercial – varieties Obaideh and Merwah], but they came to it eventually.’

Serge Hochar was fond of saying that his wines would be his legacy, and would continue to speak for him long after his death. He drowned while swimming off the Mexican coast on a family holiday with his children and grandchildren on New Year’s Eve, 2014, aged 75. The accident prompted an outpouring of affection and tributes from across the wine world. ‘It was a very difficult time,’ says Marc. ‘But our story is one of challenges, of difficulties. It’s not plain sailing. Life isn’t plain sailing. I think people understand that, and they can identify with a winery in a tough region that has gone through struggles but also triumphs. Because that’s what life is all about.’

Not a 67 Pall Mall Member? Sign up to receive a monthly edit of The Back Label by filling out your details below

WHAT

I’VE

LEARNED

Jancis Robinson MW OBE

MEET

THE

SOMM

Gastón Adolfo

ON

THE

ROAD

Richard Hemming MW in Margaret River